| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

The Kufic script (Arabic: الخط الكوفي, romanized: al-khaṭṭ al-kūfī) is a style of Arabic script, that gained prominence early on as a preferred script for Quran transcription and architectural decoration, and it has since become a reference and an archetype for a number of other Arabic scripts. It developed from the Arabic alphabet in the city of Kufa, from which its name is derived.[3] Kufic is characterized by angular, rectilinear letterforms and its horizontal orientation.[4] There are many different versions of Kufic, such as square Kufic, floriated Kufic, knotted Kufic, and others.[4] The artistic styling of Kufic led to its use in a non-Arabic context in Europe, as decoration on architecture, known as pseudo-Kufic.

History

[edit]Origin of the Kufic script

[edit]Calligraphers in the early Islamic period used a variety of methods to transcribe Quran manuscripts. Arabic calligraphy became one of the most important branches of Islamic Art. Calligraphers came out with the new style of writing called Kufic. Kufic is the oldest calligraphic form of the various Arabic scripts. The name of the script derives from Kufa, a city in southern Iraq which was considered as an intellectual center within the early Islamic period. Kufic is defined as a highly angular form of the Arabic alphabet originally used in early copies of the Quran. Sheila S. Blair suggests that "the name Kufic was introduced to Western scholarship by Jacob George Christian Adler (1756–1834)".[5] Furthermore, the Kufic script plays an important role in the development of Islamic calligraphy. In fact, "it is the first style of Islamic period writings in which the manifestation of art, delicacy and beauty are explicitly evident", says Salwa Ibraheem Tawfeeq Al-Amin.[6] The rule set for this writing was about the angular, linear shapes of the characters. In fact, "the rules that were defined at the outset of the Kufic tradition essentially remained the same throughout its lifespan", says Alain George.[7]

Usage of Kufic script

[edit]The Quran was first written in a plain, slanted, and uniform script but, when its content was formalized, a script that denoted authority emerged.[8] This coalesced into what is now known as Primary Kufic script.[8] Kufic was prevalent in manuscripts from the 7th to 10th centuries. Around the 8th century, it was the most important of several variants of Arabic scripts with its austere and fairly low vertical profile and a horizontal emphasis.[9] Until about the 11th century it was the main script used to copy the Quran.[10] Professional copyists employed a particular form of Kufic for reproducing the earliest surviving copies of the Quran, which were written on parchment and date from the 8th to 10th centuries.[11] It is distinguished from Thuluth script in its use of decorative elements whereas the latter was designed to avoid decorative motifs.[12] In place of the decorations in Kufic scripts, Thuluth used vowels.[12]

Characteristics of Kufic script

[edit]

The main characteristic of the Kufic script "appears to be the transformation of the ancient cuneiform script into the Arabic letters", according to Enis Timuçin Tan.[13] Moreover, it was characterized by figural letters that were shaped in a way to be nicely written on parchment, building and decorative objects like lusterware and coins.[14] Kufic script is composed of geometrical forms like straight lines and angles along with verticals and horizontals.[15] Originally, Kufic did not have what is known as a differentiated consonant, which means, for example, that the letters "t", "b", and "th" were not distinguished by diacritical marks and looked the same.[15] However, it is still used in Islamic countries. In later Kufic Qurans of the ninth and early tenth century, "the sura headings were more often designed with the sura title as the main feature, often written in gold, with a palmette extending into the margin", comments Marcus Fraser.[16] Its use in transcribing manuscripts has been important in the development of Kufic Script. Earlier kufic was written on manuscripts with precision which contributed to its development. For instance, "the precision achieved in practice is all more remarkable because Kufic manuscripts were not ruled", says Alain George.[17] Moreover, he explains that Kufic manuscripts were laid out with a stable number of lines per page, and these were strictly parallel and equidistant.[17] One impressive example of an early Quran manuscript, known as the Blue Quran, features gold Kufic script on parchment dyed with indigo. It is commonly attributed to the early Fatimid or Abbasid court. The main text of this Quran is written in gold ink, thus the effect on looking at the manuscript is of gold on blue. According to Marcus Fraser, "the political and artistic sophistication and financial expense of the production of the Blue Quran could only have been contemplated and achieved by a ruler of considerable power and wealth".[16]

Ornamental use of Kufic script

[edit]Ornamental Kufic became an important element in Islamic art as early as the eighth century for Quranic headings, numismatic inscriptions and major commemorative writings.[18] The Kufic script is inscribed on textiles, coins, lusterware, building and so on.[19] Coins were very important in the development of the Kufic script. In fact, "the letter strokes on coins, had become perfectly straight, with curves tending toward geometrical circularity by 86", observes Alain George.[20] As an example, Kufic is commonly seen on Seljuk coins and monuments and on early Ottoman coins. Its decorative character led to its use as a decorative element in several public and domestic buildings constructed prior to the Republican period in Turkey. Also, the current flag of Iraq (2008) also includes a kufic rendition of the takbir.

Similarly, the flag of Iran (1980) has the takbir written in white square kufic script a total of 22 times on the fringe of both the green and red bands. Kufic inscriptions were important in the emergence of textiles too, often functioning as decoration in the form of tiraz bands. According to Maryam Ekhtiar, "tiraz inscriptions were written in Kufic or floriated Kufic script, and later, in naskhi or throughout the islamic world".[21] Those inscriptions include the name of God or the ruler. As an example, the inscription inside the Dome of the Rock is written in Kufic. Throughout the text, we can notice the calligraphic line created by the reed pen which is usually a steady stroke with various thicknesses based on the changes in direction of the movement that has created it.[22] Square or geometric Kufic is a very simplified rectangular style widely used for tiling. In Iran sometimes entire buildings are covered with tiles spelling sacred names like those of God, Muhammad and Ali in square Kufic, a technique known as banna'i.[23] Moreover, there is "Pseudo-Kufic", also "Kufesque", which refers to imitations of the Kufic script, made in a non-Arabic context, during the Middle Ages or the Renaissance: "Imitations of Arabic in European art are often described as pseudo-Kufic, borrowing the term for an Arabic script that emphasizes straight and angular strokes, and is most commonly used in Islamic architectural decoration".[24]

Square Kufic

[edit]Square Kufic (Arabic: ٱلْكُوفِيّ ٱلمُرَبَّع), also sometimes known as banna'i (بَنَائِيّ, "masonry" script), is a bare Arabic writing form that developed in the 12th century.[25][26] Invented in Iraq,[27] it was prominently used in Iranian architecture with bricks and tiles functioning as pixels.[26] Legibility is not a priority of this script.[26]

The Syrian calligrapher Mamoun Sakkal described its development as an "exceptional step towards simplification in Kufic styles that evolved towards more complexity in the preceding centuries".[25]

-

Geometric Kufic from the Bou Inania Madrasa (Meknes); the text reads: بركة محمد or barakat muḥammad, i.e. "Muhammad's blessing".

-

Another example of geometric or square Kufic script, showing four instances of the name Muhammad (in black) and four times Ali (in white); often used as a tilework pattern in Islamic architecture

-

Banna'i on a minaret – a repetitive pattern of square Kufic inscriptions

-

("Allah") in red centred on the white band and the takbir written 11 times each in the Square Kufic script in white, at the bottom of the green and the top of the red band.

In recent years, this calligraphy form has been receiving more popularity for use in ornaments (such as in decorated clocks, frames, stickers), logos (that usually implies Islamic enterprises in government and private sectors), and even in freestyle Arabic calligraphy competitions. There has been a disciplined approach of creating Square Kufic calligraphy. This controlled method of creation preserved basic and accurate features of Arabic letters with few compromises, if any. A finished work can then be qualitatively judged rather than only appreciated as an abstract piece.

Configurations

[edit]While there are no restrictions to formats that Square Kufic should be written in, Square Kufic can be categorized into three most commonly used configurations.

Free Flow

[edit]The normal writing format using pixelated Arabic font. The overall shape is not limited by any shape or boundary. Although this configuration is straight forward, it is not used for most Square Kufic-related work, due to its less aesthetic appearance relative to the other configurations.

Free flow is mainly used as baseline before developed into more sophisticated configurations.

Linear

[edit]Just like free flow, the writing goes from right to left but within a justified height that conforms into a continuous rectangle. The letters including their respective dots must only leave 1 pixel apart from each other.

Linear is preferred to write long scriptures such as Quranic verses along the interior perimeter or broken into lines elegantly against mosque walls.

Spiral

[edit]While the name suggests a radial or circular form, they are usually presented in a square or rectangular shape. The 1 pixel space applies between the letters here as well. The major differences between a linear and a spiral Square Kufic calligraphy are

- Spiral has a minimum of two and up to four datums; linear only has a single datum, and

- Spiral allows letters to integrate at each corner of adjacent datums and across lines, and is only bounded by their outermost perimeter; linear letters maintain their original height even if they are warped into a spiral.

This configuration is used as a design centerpiece in buildings for shorter scriptures, name design commissions, and logos.

Other

[edit]Square Kufic calligraphy is by no means limited to the above configurations. There are many forms that are creative iterations or independent from these formats.

Gallery

[edit]-

Page from a Qur'an in Kufic style, 8th century (Surah 15: 67–74)

-

Kufic script from an early Qur'an manuscript, 8th-9th century (Surah 7: 86–87)

-

Manuscript of the Surat Maryam of the Qur'an; Kufic script on gazelle skin, 9th century (Surah 19: 83–86)

-

The leaves from this Qur'an written in gold and contoured with brown ink have a horizontal format (9th century).

-

Bifolio of Surat Al-An'am in the "Nurse’s Quran" (مصحف الحاضنة), commissioned by a patron named Fatima under the Zirid Dynasty in the early 11th century[28]

-

Abbasid Quran, Persia, late 11th / early 12th century

Kufic script elsewhere

[edit]-

Bowl with Kufic Inscription, 9th century – Brooklyn Museum

-

Bowl with Kufic calligraphy, 10th century – Brooklyn Museum

-

Bowl with Kufic calligraphy, 10th century – Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

-

11th-century gold Fatimid armlet, inscribed with good wishes in the Kufic script (Syria)

-

Kufic alphabet, from Fry's Pantographia (1799)

-

Almoravid Kufic adorning the Minbar of the Kutubiyya Mosque

-

Inscription in Kufic (743). The Walters Art Museum.

-

Drawing of an inscription of Basmala in Kufic script, 9th century. The original is in the Islamic Museum in Cairo (Inventar-Nr. 7853).

-

The flag of Iraq (2008)

-

The flag of Iraq (2004-2008)

Typefaces

[edit]Google Fonts:

Windows:

- Andalus[36]

iOS:

- Diwan Kufi[37]

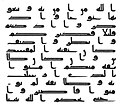

Sample text from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 1:

See also

[edit]- Ancient North Arabian script

- Ancient South Arabian script

- Hijazi script

- Maghrebi script

- Mashq script

- Muhaqqaq

- Naskh

- Nine-fold seal script (Chinese analogue to square kufic)

- Persian calligraphy

- Rayhan

- Tawqi

- Thuluth

Citations

[edit]- ^ Déroche, François. Catalogue des manuscrits arabes. Deuxième partie: manuscrits musulmans, Tome I, 1. Les manuscrits du Coran. Aux origines de la calligraphie coranique (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale, 1983), pp. 41–45.

- ^ D'Ottone Rambach, Arianna (January 2017). "The Blue Koran. A Contribution to the Debate on its Possible Origin and Date". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 8 (2). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 127–143. doi:10.1163/1878464X-00801004. S2CID 192957200.

- ^ "Kūfic script | calligraphy | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ^ a b "The Development and Spread of Calligraphic Scripts". Metmuseum.org. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ Blair, Sheila S. (2006). Islamic Calligraphy. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-7486-1212-3.

- ^ Al-Amin, Salwa Ibraheem Tawfeeq (2016). "The Origin of the Kufic Script". Magazine of Historical Studies and Archaeology (53): 3, 6.

- ^ George, Alain (2010). The Rise of Islamic Calligraphy. pp. 55, 56, 57, 65, 72. ISBN 978-0-86356-673-8.

- ^ a b Jazayeri, S. M. V. Mousavi; Michelli, Perette E.; Abulhab, Saad D. (2017). A Handbook of Early Arabic Kufic Script: Reading, Writing, Calligraphy, Typography, Monograms. New York: Blautopf Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9780998172743.

- ^ Wilson, Eva (1988). Islamic Designs for Artists and Craftspeople. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 11. ISBN 048625819X.

- ^ "Arabic scripts". British Museum. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "The Spirit of Islam: Experiencing Islam through Calligraphy". UBC Museum of Anthropology. Archived from the original on 8 November 2002. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ a b Jazayeri, S. M. V. Mousavi; Ringgenberg, Patrick; Michelli, Perette E.; Chaharmahali, Ali M.; Jazayeri, S. M. H. Mousavi (2015). Kufic Inscriptions of the Historic Grand Mosque of Shoushtar. New York: Blautopf Publishing. p. 120. ISBN 9781511537995.

- ^ Tan, Enis Timuçin (1999). "A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its relevance to Turkish Graphic Art Using Latin Fonts in the late twentieth century": 42.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Cohen, Julia (May 2014). "Early Qur'ans (8th–Early 13th Century)". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ a b Al-Amin, Salwa Ibraheem Tawfeeq (2016). "The Origin of the Kufic Script". Magazine of Historical Studies and Archaeology (53): 3, 6.

- ^ a b Fraser, Marcus (2006). Ink and Gold Islamic Calligraphy. London. pp. 28, 46. ISBN 0954901487.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b George, Alain (2010). The Rise of Islamic Calligraphy. pp. 55, 56, 57, 65, 72. ISBN 978-0-86356-673-8.

- ^ Rosen, Miriam (1983). "Islamic Calligraphy. By Yasin Hamid Safadi. Boulder: Shambhala, 1979. 142 pp.; 163 black and white plates. $8.95 paper. - Calligraphy in the Arts of the Muslim World. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979. 216 pp.; 12 color plates, 98 black and white. $25.00 cloth". Iranian Studies. 16 (1–2): 85–90. doi:10.1017/s0021086200006484. ISSN 0021-0862.

- ^ "The Arabic & Islamic Inscriptions: Examples Of Arabic Epigraphy". www.islamic-awareness.org. Retrieved 2021-02-08.

- ^ George, Alain (2010). The Rise of Islamic Calligraphy. pp. 55, 56, 57, 65, 72. ISBN 978-0-86356-673-8.

- ^ Ekhtiar, Maryam (July 2015). "Tiraz: Inscribed Textiles from the Early Islamic Period". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ George, Alain (2010). The Rise of Islamic Calligraphy. pp. 55, 56, 57, 65, 72. ISBN 978-0-86356-673-8.

- ^ Jonathan M. Bloom; Sheila Blair (2009). The Grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and architecture. Oxford University Press. pp. 101, 131, 246. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Mack, p.51

- ^ a b Sakkal, Mamoun. (2004). Principles of Square Kufic Calligraphy. Hroof Arabiyya. 4. 4-12.

- ^ a b c "Creative Arabic Calligraphy: Square Kufic". Design & Illustration Envato Tuts+. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- ^ Ibrahim Gomaa (1969). Studying the Development of Kufic Writings on Stones in Egypt in the First Five Hijri Centuries: A Comparison in Different Places of the Muslim World. Dar al-Fikr al-Araby.

- ^ "Islamic art from museums around the world". Arab News. 2020-05-18. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- ^ "Google Fonts: Noto Kufi Arabic". Google Fonts. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ "Google Fonts: Reem Kufi". Google Fonts. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ "Google Fonts: Qahiri". Google Fonts. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ "Google Fonts: Cairo". Google Fonts. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ "Google Fonts: Almarai". Google Fonts. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ "Google Fonts: Mada". Google Fonts. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ "Google Fonts: Kufam". Google Fonts. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ^ "Windows 10 font list". Microsoft Docs – Typography. Microsoft. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "Fonts included with macOS Monterey". Apple Support. 14 June 2022. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

General references

[edit]- Kosack, Wolfgang: Islamische Schriftkunst des Kufischen. Geometrisches Kufi in 593 Schriftbeispielen. Deutsch – Kufi – Arabisch. Christoph Brunner, Basel 2014, ISBN 978-3-906206-10-3.

- Mack, Rosamond E. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600, University of California Press, 2001, ISBN 0-520-22131-1

External links

[edit]- Square Kufic lectures: alphabet (stylized), examples, square designs

- Kufic manuscript alphabet

- On the Origins of the Kufic Script

- Kufic Script

- Square Kufic Script

- Square Kufic

- Square Kufic explained